In the relentless pursuit of cleaner, more efficient transportation, hybrid vehicle technology has emerged as a crucial bridge between traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles and fully electric vehicles (EVs). At the heart of hybrid innovation lie various architectural designs, each with its unique approach to combining gasoline power with electric propulsion. Among these, the parallel hybrid configuration stands out, particularly for its distinctive advantage of direct power delivery. This article delves deep into the mechanics of parallel hybrid systems, contrasting them with series hybrid configurations, and illuminates why the parallel approach, especially its ability to directly couple the engine and electric motor to the wheels, offers compelling benefits for engineering the future of mobility.

Understanding the nuances between these two primary hybrid architectures is essential for appreciating the advancements in automotive engineering. While both aim to reduce fuel consumption and emissions, their methodologies for achieving this vary significantly, impacting everything from driving dynamics and efficiency across different speeds to the overall complexity and cost of the vehicle. Join us as we explore the intricate world of hybrid powertrains, focusing on the sophisticated engineering behind parallel hybrids and their pivotal role in shaping a more sustainable automotive landscape.

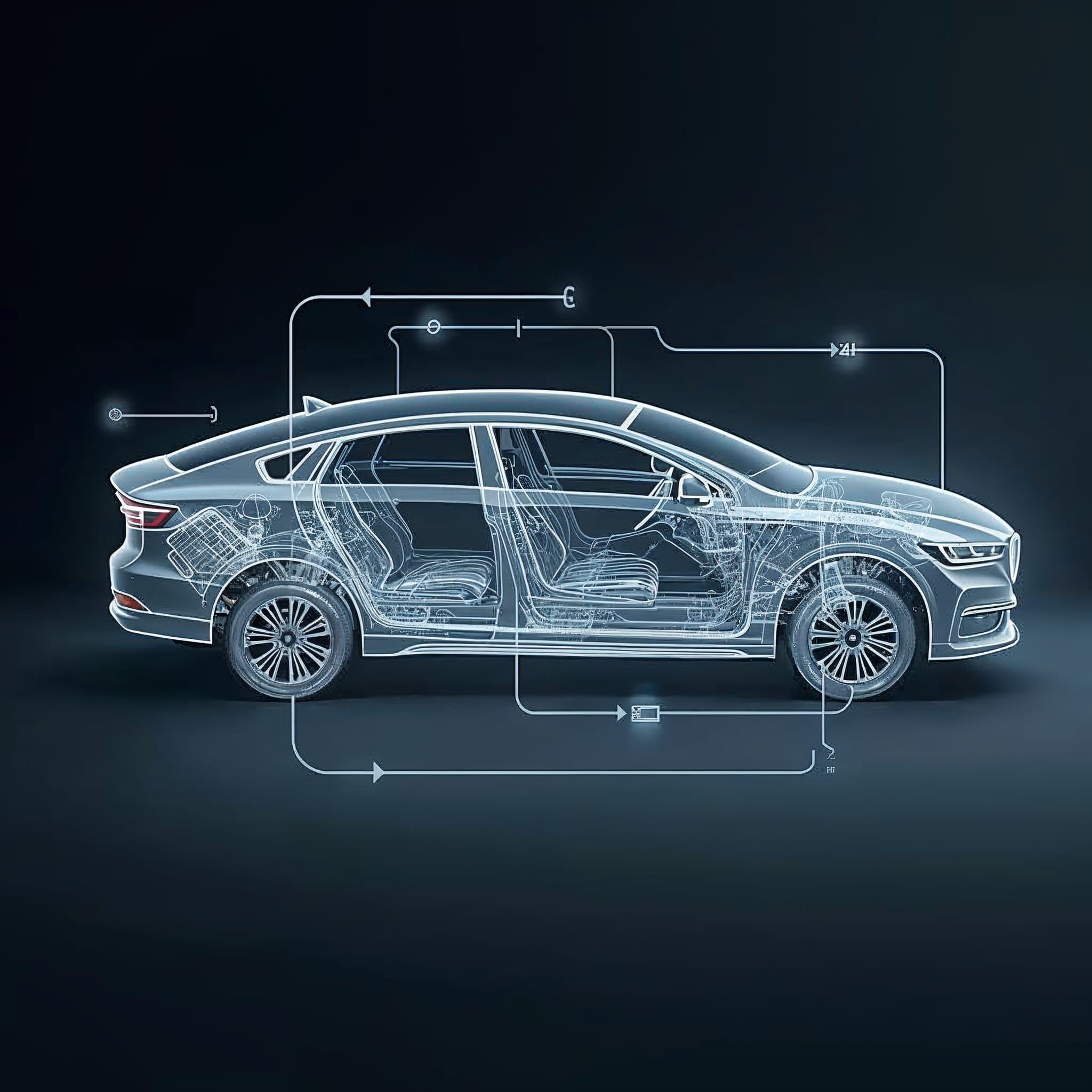

Understanding Hybrid Vehicle Architectures

The concept of a hybrid vehicle, at its core, revolves around utilizing at least two distinct power sources to propel the vehicle. Traditionally, this has meant combining a gasoline-powered internal combustion engine with an electric motor powered by a battery. The strategic integration of these two systems allows hybrids to overcome the limitations of each individually, leading to improved fuel economy, reduced emissions, and often enhanced performance characteristics like instantaneous torque delivery.

The Core Concept of Hybrid Powertrains

A hybrid powertrain intelligently manages power flow between the ICE and the electric motor, adapting to varying driving conditions. For instance, at low speeds or during acceleration, the electric motor can provide silent, zero-emission propulsion. During cruising or heavy acceleration, the ICE might take over or work in tandem with the electric motor for maximum power. Crucially, hybrids employ regenerative braking, where the electric motor acts as a generator during deceleration, converting kinetic energy typically lost as heat into electricity to recharge the battery. This cycle of energy recovery and reuse is a cornerstone of hybrid efficiency.

The strategic combination of power sources allows for operations such as engine shut-off at idle (start-stop systems), electric-only driving, and power boosting, all contributing to a more efficient and environmentally friendly vehicle. The sophistication lies not just in having two power sources, but in the intelligent control systems that orchestrate their interaction seamlessly, often imperceptibly to the driver.

Why Hybrid? The Quest for Efficiency

The primary motivation behind hybrid vehicle development is efficiency. Internal combustion engines are highly efficient within specific operating ranges but become significantly less efficient at low speeds, during idling, or when subjected to frequent stop-and-go conditions. Electric motors, conversely, are very efficient at low speeds and can deliver peak torque almost instantly. By combining these, hybrids can leverage the strengths of each. For example, in city driving, the electric motor can handle propulsion, eliminating the inefficient operation of the ICE. On the highway, the ICE can operate at its most efficient speed, supplemented by the electric motor when extra power is needed for acceleration or hill climbing.

Beyond fuel efficiency, hybrids contribute significantly to reducing tailpipe emissions, particularly greenhouse gases and local air pollutants. This dual benefit of economic savings for consumers and environmental advantages for society has driven the rapid adoption and continuous innovation in hybrid technology, paving the way for the exploration of diverse architectural configurations that optimize for different driving scenarios and performance goals.

Series Hybrid Configuration: The Electric Drive

The series hybrid configuration represents a fundamental approach to integrating electric and combustion power, often described as an “electric vehicle with a range extender.” In this setup, the internal combustion engine never directly drives the wheels. Instead, its sole purpose is to power a generator, which then produces electricity. This electricity can either charge the vehicle’s battery pack or directly power an electric motor that, in turn, drives the wheels. Let’s explore its operational mechanics and inherent advantages and limitations.

How Series Hybrids Work

In a series hybrid system, the power flow is always sequential or “in series.” The ICE is mechanically coupled to a generator, forming what is often referred to as a “generator set.” This generator converts the mechanical energy from the engine into electrical energy. The electrical energy then takes one of two paths:

- It can flow to a battery pack, recharging it for later use.

- It can flow directly to one or more electric motors that are mechanically connected to the vehicle’s drive wheels.

The electric motor is the sole means of propelling the vehicle. The engine’s role is essentially that of an onboard power plant, providing electricity when the battery’s charge is low or when the power demand exceeds what the battery alone can supply. This design means that the engine can operate within its most efficient RPM range, regardless of the vehicle’s speed, as it’s not directly tied to the wheels’ rotation. This characteristic makes series hybrids particularly effective in urban driving environments where stop-and-go traffic is common, and the ability to run purely on electric power is advantageous.

Examples of vehicles that have utilized or closely resemble series hybrid principles include the Chevrolet Volt (in its primary operational mode when the battery is depleted) and some early diesel-electric locomotives, which also function on a similar principle of using an engine to generate electricity for electric traction motors.

Advantages and Limitations of Series Systems

The series hybrid configuration offers several distinct advantages:

- Simplified Drivetrain: Without a direct mechanical link between the engine and wheels, the transmission system can be significantly simplified or even eliminated in some designs, reducing mechanical complexity and potentially manufacturing costs.

- Optimal Engine Operation: The ICE can be run at its most efficient speed (sweet spot) for power generation, irrespective of vehicle speed, leading to better fuel economy in certain scenarios, especially at lower speeds or during heavy power demand.

- Smooth Electric Drive: The driving experience closely mimics that of an electric vehicle, offering quiet, smooth, and torquey acceleration from a standstill, as all propulsion comes from the electric motor.

- Effective for Range Extension: They excel as range extenders for electric vehicles, providing peace of mind against range anxiety by generating electricity on the go.

However, series hybrids also come with notable limitations:

- Double Energy Conversion Losses: This is arguably the most significant drawback. Energy from the fuel is first converted to mechanical energy by the engine, then to electrical energy by the generator, and finally back to mechanical energy by the electric motor. Each conversion step involves efficiency losses, meaning a portion of the original energy from the fuel is lost as heat. This can make series hybrids less efficient than parallel hybrids at higher speeds or under sustained highway driving conditions where direct mechanical drive is more efficient.

- Larger/More Powerful Components: Both the generator and the electric motor must be sized to handle the full power requirements of the vehicle, potentially leading to larger and heavier components compared to parallel systems where power can be shared.

- Battery Reliance: The system relies heavily on the battery’s ability to store and deliver power efficiently. If the battery is depleted and the engine is operating sub-optimally to generate power, overall efficiency can suffer.

Despite these limitations, series hybrids provide a valuable solution for specific use cases, particularly where electric-only driving or quiet operation is prioritized, and the driving cycle primarily involves lower speeds and frequent stops.

Parallel Hybrid Configuration: Direct Power and Flexibility

In contrast to the series hybrid’s indirect power delivery, the parallel hybrid system offers a more integrated approach, allowing both the internal combustion engine and the electric motor to directly propel the vehicle, either individually or simultaneously. This direct mechanical connection is the cornerstone of its efficiency and flexibility, making it a popular choice for a wide range of hybrid vehicles today.

The Mechanics of Parallel Hybrid Operation

The defining characteristic of a parallel hybrid is the ability of both the ICE and the electric motor to transmit power directly to the wheels. This is typically achieved through a shared transmission system, which can be a conventional automatic, a manual, a continuously variable transmission (CVT), or a specialized hybrid transmission. The electric motor is often positioned between the engine and the transmission, or sometimes integrated directly within the transmission unit itself.

Here’s how power delivery typically works in a parallel hybrid:

- Electric-Only Mode (EV Mode): At low speeds, during light acceleration, or when coasting, the electric motor can power the wheels independently, with the ICE shut off. This provides silent, zero-emission driving and is particularly efficient in stop-and-go city traffic.

- Engine-Only Mode: At higher speeds or during sustained cruising, the ICE can power the wheels directly, with the electric motor disengaged or used for supplemental charging. This leverages the ICE’s optimal efficiency range on the highway, avoiding the double conversion losses seen in series hybrids.

- Combined Power Mode (Hybrid Mode): For maximum acceleration, hill climbing, or when the battery state of charge (SoC) allows, both the ICE and the electric motor can work together, delivering combined power to the wheels. The electric motor provides immediate torque fill, enhancing overall performance and responsiveness.

- Regenerative Braking: During deceleration or braking, the electric motor acts as a generator, converting kinetic energy into electricity to recharge the battery. This feature is common across most hybrid designs and significantly boosts overall efficiency.

The seamless transition between these modes, managed by sophisticated electronic control units (ECUs), is crucial for optimizing fuel economy and driving performance. The mechanical coupling allows for a very direct and efficient transfer of power from the engine to the wheels when needed, minimizing energy losses.

Key Advantages of Direct Power Delivery

The direct power delivery capability of parallel hybrids offers several significant advantages:

- Superior Highway Efficiency: By allowing the ICE to directly drive the wheels, parallel hybrids avoid the double energy conversion losses inherent in series systems when the engine is the primary power source. This makes them significantly more efficient than series hybrids during sustained highway driving or under conditions where the ICE is operating at its optimal cruise speed.

- Enhanced Performance and Responsiveness: The ability of the electric motor to provide instantaneous torque alongside the ICE’s power output results in a more robust and responsive driving experience. The electric motor can “fill in” torque gaps during gear changes or provide an immediate boost for acceleration, often making the vehicle feel more powerful than its engine size might suggest.

- Greater Flexibility in Operation: Parallel hybrids can operate in a wider variety of modes, adapting more effectively to different driving conditions. Whether it’s pure electric in the city, pure engine on the highway, or a combination for demanding situations, the system can choose the most efficient power source or combination.

- Potentially Smaller Components: In some parallel designs, the electric motor and ICE can be sized to complement each other, meaning neither needs to be independently capable of providing full vehicle power. This can lead to lighter and more compact powertrain components compared to series hybrids, where the electric motor must be powerful enough for sole propulsion.

- Familiar Driving Dynamics: Because the engine can directly drive the wheels through a transmission, the driving feel of a parallel hybrid can be more familiar to drivers accustomed to traditional gasoline cars, particularly concerning acceleration and engine sound at higher speeds.

The flexibility and efficiency derived from direct power delivery make parallel hybrid systems a highly versatile and compelling choice for modern automotive applications, balancing fuel economy with traditional driving dynamics and performance.

Comparing Power Flow and Efficiency: Series vs. Parallel

A deeper look into the power flow dynamics and energy conversion efficiencies provides critical insights into why parallel hybrids often hold an advantage in overall fuel economy, especially under varied driving conditions. The key distinction lies in how mechanical energy from the engine reaches the wheels and the number of conversions it undergoes.

Energy Conversion Losses in Series Hybrids

As previously discussed, the series hybrid configuration is characterized by its sequential power flow: ICE generates mechanical power, which is converted into electrical power by a generator, and this electrical power then drives an electric motor that propels the vehicle. This process, while offering certain operational benefits, inherently introduces multiple stages of energy conversion, each incurring losses.

Consider the energy path from the fuel tank to the wheels:

- Fuel to Mechanical (ICE): The internal combustion engine converts the chemical energy in fuel into mechanical rotational energy. Modern ICEs typically operate at peak thermal efficiencies of around 35-40%, meaning 60-65% of the fuel’s energy is lost as heat.

- Mechanical to Electrical (Generator): The mechanical energy from the ICE is then fed into a generator, which converts it into electrical energy. Generators are highly efficient, often exceeding 90-95% efficiency, but still, a percentage of energy is lost as heat.

- Electrical to Electrical (Battery/Inverter): If the electricity charges the battery, there are charging and discharging losses (typically 5-10%). If it goes directly to the motor, there are inverter losses (a few percent).

- Electrical to Mechanical (Electric Motor): Finally, the electrical energy powers the traction motor, which converts it back into mechanical energy to drive the wheels. Electric motors are very efficient, often 90-95% efficient, but again, there are losses.

When these efficiencies are multiplied, the cumulative efficiency of the entire powertrain can drop significantly. For example, if the ICE is 35% efficient, the generator 90% efficient, and the motor 90% efficient, the overall efficiency of energy transfer from fuel to wheels via this path is roughly 0.35 * 0.90 * 0.90 = 28.35%. This ‘double conversion’ penalty is most pronounced when the ICE is actively providing power for propulsion, making series hybrids less efficient for sustained, higher-speed driving where the engine would otherwise be directly coupled to the wheels.

Mechanical Efficiency of Parallel Hybrids

Parallel hybrid systems, on the other hand, circumvent this double conversion loss in scenarios where the internal combustion engine is the primary power source. Because the ICE can directly drive the wheels through the transmission, the energy path is much shorter and more direct:

- Fuel to Mechanical (ICE): Similar to the series hybrid, the ICE converts fuel energy into mechanical energy, with associated thermal losses.

- Mechanical to Mechanical (Transmission/Driveline): The mechanical energy from the ICE is then transmitted directly to the wheels via the transmission and driveline. While transmissions and drivelines have their own losses (typically 5-15%), this single mechanical path is inherently more efficient than multiple electrical conversions.

When the electric motor is assisting or propelling the vehicle, its energy path involves electrical-to-mechanical conversion, similar to the final stage of a series hybrid. However, the critical advantage for parallel systems is their ability to bypass the generator and battery storage path when the ICE is most efficient at driving the wheels directly. This significantly boosts overall efficiency, particularly during highway cruising, where the engine can operate at its optimal RPM for an extended period, directly coupling its power to the wheels with minimal intermediate losses.

Furthermore, parallel hybrids can leverage the electric motor for “torque fill,” instantly providing additional power during acceleration or transient demands, allowing the ICE to remain in its more efficient operating range or even momentarily shut off. This dynamic interplay between the engine and motor, facilitated by direct mechanical linkage, provides a highly versatile and often more efficient solution across a broader spectrum of driving conditions compared to the series configuration. This is why many mainstream hybrid vehicles, including most mild hybrids and full hybrids, employ a parallel or a sophisticated series-parallel (power-split) architecture that incorporates direct mechanical drive capabilities.

Advanced Parallel Hybrid Designs and Modern Implementations

The parallel hybrid architecture is not a monolithic design; it encompasses a spectrum of configurations, each tailored to different performance, efficiency, and cost objectives. These designs range from simple mild hybrids to complex plug-in hybrids, all leveraging the fundamental principle of both the engine and motor having direct access to the drivetrain.

Mild Parallel Hybrids (MHEV)

Mild hybrids represent the simplest and often most cost-effective form of parallel hybridization. They typically feature a smaller electric motor, often integrated as a beefed-up starter-generator (Belt-driven Starter Generator or BSG, or Crankshaft-mounted Starter Generator or CSG), and a relatively small battery pack (e.g., 48-volt system). The electric motor cannot propel the vehicle independently for any significant distance; its primary roles are:

- Enhanced Start/Stop: Providing smoother and quicker engine restarts.

- Torque Assist/Boost: Offering a modest power boost during acceleration, reducing the load on the ICE.

- Regenerative Braking: Recovering kinetic energy more effectively than a conventional alternator.

- Powering Accessories: Running vehicle accessories when the engine is off or assisting during high electrical loads.

MHEVs provide incremental improvements in fuel economy (typically 10-15%) and emissions, primarily by making the ICE more efficient in its operation. They are popular because they integrate relatively easily into existing vehicle platforms without requiring a complete redesign of the drivetrain. Examples include many modern Audi, Mercedes-Benz, and Ram vehicles equipped with 48V systems.

Full Parallel Hybrids (FHEV)

Full hybrids, often simply called “hybrids,” offer a more substantial level of electrification than mild hybrids. They feature a larger electric motor, a larger battery pack, and often a more sophisticated transmission system capable of managing power flow from both sources. In a full parallel hybrid, the electric motor is powerful enough to propel the vehicle independently for short distances and at low speeds (typically up to 25-40 mph), as well as provide significant assistance to the ICE. Power flow can be entirely electric, entirely engine, or a combination of both.

These systems require more complex control units and often a specialized hybrid transmission, such as Toyota’s Hybrid Synergy Drive (HSD) which, while featuring a planetary gearset that allows for series operation, is fundamentally a power-split or series-parallel system that enables direct mechanical drive under many conditions. Other full parallel systems, like Honda’s Integrated Motor Assist (IMA) in earlier models, featured a simpler design with an electric motor sandwiched between the engine and transmission, providing torque assist and regenerative braking but less robust EV-only capability than HSD. Modern full parallel systems continue to evolve, offering improved electric-only range and better integration.

Plug-in Parallel Hybrids (PHEV)

Plug-in hybrids represent the most advanced form of parallel hybridization, designed to maximize electric-only driving range. They integrate a much larger battery pack (typically 8 kWh to 20+ kWh) and a more powerful electric motor than full hybrids, allowing them to travel significant distances (20-50+ miles) on electric power alone. The key differentiating feature is the ability to charge the battery by plugging into an external electricity source, similar to a pure EV.

PHEVs function as full parallel hybrids, but with an extended EV mode. They can operate purely on electricity for daily commutes, with the ICE serving as a backup for longer trips or when battery power is depleted. This offers the best of both worlds: zero-emission electric driving for everyday use and the flexibility of gasoline power for extended range without range anxiety. Many modern PHEVs, like the Toyota RAV4 Prime, Ford Escape PHEV, and Hyundai Santa Fe PHEV, utilize parallel-based architectures to efficiently blend electric and gasoline power for both performance and remarkable fuel economy. The ability to directly deliver power from both sources is crucial for managing the complex energy demands of a vehicle capable of operating extensively in EV mode while also offering strong hybrid performance.

The Future of Hybrid Powertrains: Evolving Parallel Systems

The trajectory of hybrid technology is one of continuous evolution, with parallel systems at the forefront of innovation due to their inherent flexibility and efficiency. Future developments are focused on optimizing every aspect of the powertrain, from power delivery and energy storage to vehicle intelligence and grid integration.

Integration with Advanced Transmissions

Future parallel hybrid systems will see even deeper integration with advanced transmission technologies. This includes sophisticated multi-speed transmissions specifically designed for hybrids, which can more precisely match engine RPM to vehicle speed and power demands, further minimizing fuel consumption. Instead of just adding a motor, the entire transmission is being re-imagined as a hybrid component. For instance, some manufacturers are developing dedicated hybrid transmissions (DHTs) that combine multiple electric motors with fewer traditional gears, allowing for incredibly flexible power-split capabilities that transcend simple series or parallel classifications, often leveraging the best of both. These DHTs can operate in full electric mode, blend engine and motor power seamlessly, and even allow the engine to power a generator for battery charging while still propelling the vehicle, similar to a power-split configuration. This level of integration promises to refine direct power delivery, ensuring that the most efficient power path is always selected, whether it involves direct engine drive, electric drive, or a combination.

Furthermore, advancements in clutch technology and software control will enable even smoother and faster transitions between electric, engine, and combined modes, enhancing both efficiency and driver experience. The goal is to maximize the time spent in the most efficient operating window for both the ICE and the electric motor, adapting intelligently to real-time driving conditions.

Bi-directional Charging and Smart Grids

A significant area of future development for plug-in parallel hybrids (PHEVs) is the expansion of bi-directional charging capabilities, often referred to as Vehicle-to-Grid (V2G) or Vehicle-to-Home (V2H) technology. Currently, most PHEVs can only charge their batteries from the grid. Bi-directional charging would allow the vehicle to not only draw electricity from the grid but also feed electricity back into it or power a home during peak demand or outages.

This capability transforms PHEVs into mobile energy storage units, making them an integral part of future smart grids. For parallel hybrids, which already manage complex power flows between two distinct power sources and the wheels, integrating bi-directional charging adds another layer of sophistication to their energy management system. Such advancements would:

- Enhance Grid Stability: By storing renewable energy when abundant and releasing it during shortages.

- Provide Economic Benefits: Owners could potentially sell electricity back to the grid during peak pricing hours.

- Increase Energy Resilience: Vehicles could power homes during blackouts, acting as a personal generator.

Implementing V2G/V2H will require advanced power electronics, communication protocols between the vehicle and the grid, and robust battery management systems. As parallel hybrids already possess the fundamental architecture for managing energy flow, they are well-positioned to evolve into powerful components of a decentralized energy future, offering more than just transportation but also energy independence and grid support.

The future of parallel hybrid technology is bright, characterized by increasingly sophisticated power management, tighter integration with advanced mechanical systems, and a crucial role in the broader energy ecosystem. These developments promise even greater efficiency, performance, and utility, firmly cementing parallel hybrids as a cornerstone of sustainable personal mobility.

Comparison Tables

To summarize the key differences and characteristics, here are two tables providing a direct comparison between series and parallel hybrid systems, along with an overview of their power delivery attributes.

| Feature | Series Hybrid Configuration | Parallel Hybrid Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Engine Connection to Wheels | Indirect (Engine powers generator, generator powers motor, motor powers wheels) | Direct (Engine can mechanically drive wheels, often with motor assistance) |

| Primary Propulsion Source | Always Electric Motor | Electric Motor, Engine, or both simultaneously |

| Energy Conversion Stages (Engine to Wheels) | Multiple: Mechanical (ICE) → Electrical (Generator) → Electrical (Battery/Inverter) → Mechanical (Motor) | Direct: Mechanical (ICE) → Mechanical (Driveline); or Electrical (Motor) → Mechanical (Driveline) |

| Efficiency at Highway Speeds | Lower (due to double energy conversion losses) | Higher (due to direct mechanical drive, bypassing electrical conversion) |

| Efficiency in City Driving (Stop-and-Go) | High (engine can operate at optimal RPM or shut off; pure EV mode is efficient) | High (engine can shut off; pure EV mode is efficient; regenerative braking) |

| System Complexity | Potentially simpler transmission (no direct engine-wheel link) but requires large generator/motor | More complex power coupling/transmission to blend power sources |

| Driving Feel | More like an EV (smooth, quiet electric propulsion) | More like a traditional car (engine sound, direct mechanical feel, but with electric boost) |

| Typical Use Cases | Urban driving, range-extended EVs, commercial vehicles with specific power demands | General passenger cars, SUVs, varying driving conditions (city/highway balance) |

| Component/Aspect | Series Hybrid Impact | Parallel Hybrid Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) Size | Can be smaller, optimized for specific RPM for generator, less direct vehicle load | Generally larger than series, directly coupled to vehicle load, sized for primary propulsion needs |

| Electric Motor/Generator Size | Motor and generator must be sized to handle full vehicle power output, potentially larger | Motor can be sized for assist, or primary EV drive; ICE and motor can share load, potentially smaller individual components |

| Battery Capacity (Non-PHEV) | Moderate capacity needed to buffer generated power and sustain EV mode | Moderate capacity, primarily for energy recovery and temporary EV operation |

| Transmission System | Can be simplified or single-speed (motor drives wheels) | More complex, requires clutches/gears to combine engine and motor power to wheels |

| Fuel Economy Improvement | Significant in city driving; less so on highway due to conversion losses | Significant across varied driving conditions, particularly strong on highway |

| Manufacturing Cost | Can be lower for simpler drivetrain, but higher for powerful electric components | Can be higher due to complex power coupling/transmission, but economies of scale exist |

| Emissions Reduction | Good in urban environments due to engine optimization and EV mode | Excellent across all driving conditions, aided by engine efficiency and robust EV mode |

Practical Examples

Real-world examples offer the clearest illustration of how parallel hybrid principles are applied and why they have gained widespread adoption. While some systems incorporate elements of both series and parallel operation (often termed series-parallel or power-split), their core strength often lies in their ability to leverage direct power delivery.

Toyota’s HSD (Hybrid Synergy Drive) – A Parallel-Series Masterpiece

Perhaps the most recognized and successful hybrid system globally, Toyota’s Hybrid Synergy Drive (HSD), found in models like the Prius, Camry Hybrid, and RAV4 Hybrid, is technically a “power-split” or “series-parallel” hybrid. While it contains elements that allow it to behave like a series hybrid (e.g., the engine can power a generator to charge the battery or run the motor), its genius lies in the planetary gearset that acts as an electronically controlled continuously variable transmission (eCVT).

This unique setup allows the HSD to operate very effectively as a parallel hybrid. At higher speeds, the planetary gearset directly couples the internal combustion engine to the drive wheels, allowing for highly efficient direct power delivery, significantly reducing the energy conversion losses that would occur in a pure series system. The electric motor simultaneously assists, provides torque fill, and manages regenerative braking. The ability to directly connect the engine to the wheels for optimal cruising efficiency is a major reason for HSD’s legendary fuel economy across mixed driving conditions, demonstrating the paramount importance of direct power delivery in a sophisticated hybrid architecture.

Honda’s IMA (Integrated Motor Assist) – A Pure Parallel Approach

Earlier Honda hybrid models, such as the Civic Hybrid and Insight (first and second generations), utilized the Integrated Motor Assist (IMA) system, which is a classic example of a “true” parallel hybrid. In the IMA system, a thin electric motor/generator is sandwiched directly between the engine and the conventional transmission. This allows the electric motor to always operate in parallel with the engine, assisting it directly in driving the wheels.

Key characteristics of Honda’s IMA:

- Direct Engine-to-Wheel Connection: The engine is always mechanically connected to the wheels. The electric motor primarily acts as an assist, providing supplementary torque during acceleration and capturing energy during deceleration through regenerative braking.

- Limited EV-Only Mode: Unlike full parallel hybrids with stronger EV capabilities, IMA systems typically had very limited (or no sustained) pure electric driving capability. The motor would assist, but the engine would typically be running if the vehicle was in motion.

- Simpler Design: Compared to Toyota’s HSD, IMA was mechanically simpler, using a conventional manual or automatic transmission, with the electric motor integrated. This simplicity contributed to lower manufacturing costs.

While later Honda hybrids (like the current Accord Hybrid and CR-V Hybrid) have moved towards a more advanced two-motor system that sometimes acts like a series hybrid at lower speeds and a parallel hybrid at higher speeds, the IMA demonstrated the clear advantages of a direct parallel connection for achieving fuel efficiency gains through engine assistance and robust regenerative braking.

Modern PHEV Implementations

Many contemporary Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) heavily rely on parallel hybrid principles to deliver their impressive electric range and combined efficiency. Manufacturers like Hyundai (e.g., Santa Fe PHEV, Tucson PHEV), Kia (e.g., Sorento PHEV, Sportage PHEV), Ford (e.g., Escape PHEV, Kuga PHEV), and Stellantis brands (e.g., Jeep Wrangler 4xe, Chrysler Pacifica Hybrid) employ parallel hybrid architectures in their PHEVs. These systems typically feature:

- Powerful Electric Motors: Capable of providing significant all-electric driving range (often 20-50 miles or more) at higher speeds than typical FHEVs.

- Larger Battery Packs: To support the extended EV range, these vehicles have significantly larger batteries than non-plug-in hybrids.

- Sophisticated Control: The Electronic Control Unit (ECU) intelligently manages the interaction between the ICE, electric motor, and battery, optimizing for either pure EV driving, blended power, or high-efficiency direct engine drive when the battery is depleted or highway speeds are reached.

For example, the Jeep Wrangler 4xe uses a parallel hybrid architecture with two electric motors (one acting as a starter-generator and another integrated into the transmission) paired with a turbocharged gasoline engine. This setup allows for electric-only off-roading, strong combined power for on-road performance, and efficient highway cruising where the engine can directly drive the wheels. The ability of the parallel system to offer both robust EV-only capability and efficient direct mechanical power delivery is precisely what makes these modern PHEVs so versatile and appealing to a broad range of consumers.

These examples underscore that whether in basic assist systems, sophisticated power-split configurations, or advanced plug-ins, the principle of allowing the internal combustion engine to directly contribute power to the wheels alongside or independently of the electric motor remains a cornerstone of efficient and high-performing hybrid vehicle design.

Frequently Asked Questions About Hybrid Systems

Q: What is the fundamental difference between series and parallel hybrid systems?

A: The fundamental difference lies in how the internal combustion engine (ICE) connects to the wheels. In a series hybrid, the ICE never directly drives the wheels; it only generates electricity for an electric motor, which then powers the wheels. In contrast, a parallel hybrid allows both the ICE and the electric motor to directly drive the wheels, either individually or simultaneously, via a shared transmission system. This direct mechanical connection for the ICE is the defining characteristic of a parallel hybrid.

Q: Which hybrid system is generally more efficient, series or parallel?

A: This depends heavily on the driving conditions. Series hybrids tend to be more efficient in city driving with frequent stops and low speeds because the engine can operate at its most efficient RPM to generate electricity, or the vehicle can run purely on electric power. However, parallel hybrids generally offer superior efficiency at higher, sustained highway speeds. This is because their direct mechanical link between the engine and the wheels avoids the “double energy conversion losses” (mechanical to electrical to mechanical) that occur when a series hybrid’s engine is running for propulsion.

Q: Are all hybrid vehicles either strictly series or strictly parallel?

A: Not always. While series and parallel are the two primary classifications, many modern hybrid systems, especially those found in popular vehicles like the Toyota Prius (Hybrid Synergy Drive), are often described as “series-parallel” or “power-split” hybrids. These sophisticated designs combine elements of both, allowing for the flexibility to operate in series mode (e.g., engine charging battery while motor drives wheels) or parallel mode (e.g., engine directly driving wheels, assisted by motor) depending on the driving situation, thereby optimizing efficiency across a wider range of conditions.

Q: What is a Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), and how does it relate to parallel hybrids?

A: A Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV) is a type of hybrid that features a larger battery pack than a standard (full) hybrid and can be recharged by plugging into an external electricity source. Many PHEVs are built upon a parallel hybrid architecture, meaning they leverage the direct power delivery advantages of parallel systems. This allows them to drive significant distances (typically 20-50+ miles) on electric power alone, making them ideal for daily commutes, while still retaining the gasoline engine for longer trips, effectively offering the best of both EV and hybrid worlds.

Q: Can a parallel hybrid run on electricity alone?

A: Yes, full parallel hybrids and plug-in parallel hybrids are designed to run on electricity alone for certain periods. Full hybrids can typically operate in electric-only mode at lower speeds and for short distances (a few miles). Plug-in parallel hybrids, with their larger batteries and more powerful electric motors, can achieve much longer electric-only ranges (many tens of miles) and at higher speeds, making pure EV driving a practical reality for daily commutes.

Q: How does regenerative braking work in parallel hybrid systems?

A: Regenerative braking is a key feature in both series and parallel hybrids. In a parallel hybrid, when the driver lifts their foot off the accelerator or applies the brakes, the electric motor reverses its function, acting as a generator. Instead of using friction brakes to dissipate kinetic energy as heat, the motor converts this kinetic energy into electricity, which is then stored in the battery pack. This recovered energy can then be used later to power the electric motor, significantly improving overall fuel efficiency and reducing brake wear. The direct mechanical linkage allows for efficient energy recovery directly through the drivetrain.

Q: Are parallel hybrids more complex to maintain than traditional gasoline cars?

A: Parallel hybrids do have additional components compared to conventional gasoline cars (electric motor, battery pack, power electronics). However, modern hybrid systems are designed for high reliability and durability. Maintenance procedures for the gasoline engine components are largely similar to conventional cars. Hybrid-specific components, like the battery and electric motor, are often designed for the lifetime of the vehicle and generally require less routine maintenance. Specialized diagnostic tools might be needed for hybrid systems, but overall, maintenance costs are often comparable or even lower due to less wear on traditional components like brake pads (thanks to regenerative braking) and reduced engine run-time.

Q: Why don’t all hybrid cars use a purely parallel design?

A: While parallel hybrids offer significant advantages, especially in highway efficiency and performance, purely parallel designs can be less optimal in specific scenarios. For instance, in heavy city traffic or for very low-speed operations, a series-like operation (where the engine runs at its most efficient point to generate electricity, even if the vehicle speed is very low) can be more efficient. The complexity of mechanically coupling and managing power flow from both sources can also be a design challenge. Power-split (series-parallel) systems emerged as a way to combine the benefits of both, offering flexibility that a pure parallel design might lack in certain driving conditions.

Q: What is “torque fill” in the context of parallel hybrids?

A: “Torque fill” refers to the electric motor’s ability to provide immediate, supplemental torque during periods when the internal combustion engine’s output might be lagging or inconsistent, such as during acceleration from a stop, at low RPMs, or during gear shifts. Since electric motors deliver maximum torque from zero RPM, they can instantly fill these “torque gaps,” resulting in smoother, more responsive, and more powerful acceleration. This enhances the overall driving experience and helps the ICE operate more efficiently by allowing it to avoid less efficient, high-load operating points.

Q: What role do parallel hybrids play in the transition to fully electric vehicles?

A: Parallel hybrids, particularly PHEVs, play a crucial transitional role. They offer consumers the experience of electric driving (silent, immediate torque, zero emissions for daily commutes) without the range anxiety often associated with pure EVs. They help familiarize drivers with charging habits and electric vehicle dynamics. By significantly reducing reliance on fossil fuels and lowering emissions, they serve as a practical, widely adopted solution that bridges the gap, allowing infrastructure and consumer acceptance for EVs to grow, while still providing a robust, efficient solution for current mobility needs.

Key Takeaways: Engineering the Future

- Direct Power Delivery is Key: Parallel hybrid systems stand out for their ability to allow both the internal combustion engine and the electric motor to directly drive the wheels, optimizing power flow and efficiency.

- Superior Highway Efficiency: By avoiding the multiple energy conversion losses of series hybrids, parallel systems are generally more fuel-efficient during sustained high-speed driving.

- Enhanced Performance and Flexibility: The direct mechanical coupling enables robust acceleration through combined power and offers diverse operational modes, from pure EV to pure engine drive.

- Diverse Implementations: From mild hybrids (MHEV) providing basic assistance to full hybrids (FHEV) with substantial EV capability and plug-in hybrids (PHEV) offering extended electric range, parallel architectures are highly adaptable.

- Advanced Power Management: Modern parallel systems, including sophisticated series-parallel designs like Toyota’s HSD, continuously optimize energy distribution for maximum efficiency across all driving conditions.

- Future Integration: The evolution of parallel hybrids includes deeper integration with advanced transmissions and bi-directional charging capabilities, positioning them as key players in future smart energy grids.

- Bridge to Electrification: Parallel hybrids, especially PHEVs, serve as a vital stepping stone in the global transition towards fully electric vehicles, offering a balance of efficiency, performance, and practicality.

Conclusion: The Path Forward for Hybrid Technology

The journey through the mechanics of hybrid vehicle systems reveals a fascinating landscape of engineering innovation, where the quest for efficiency and sustainability drives constant evolution. Among the diverse architectures, the parallel hybrid system, with its inherent advantage of direct power delivery, has proven to be a particularly robust and versatile solution. Its ability to mechanically couple both the internal combustion engine and the electric motor to the drive wheels offers a compelling balance of fuel economy, performance, and flexibility that resonates with a broad spectrum of drivers and driving conditions.

From the subtle assistance of mild hybrids to the extended electric range of plug-in parallel hybrids, the principle of direct power delivery minimizes energy losses, especially at highway speeds, and enhances the overall driving experience with responsive acceleration. As we’ve explored, systems like Toyota’s HSD and modern PHEV implementations are testament to the sophisticated engineering that optimizes power flow, making hybrid technology increasingly seamless and effective.

Looking ahead, the evolution of parallel hybrid powertrains is poised to continue. Innovations in advanced transmissions, smarter control algorithms, and the integration of bi-directional charging capabilities promise to unlock even greater efficiencies and expand the utility of these vehicles beyond mere transportation. Parallel hybrids are not just a stepping stone; they are a critical component of our immediate and near-future sustainable mobility strategy, offering a practical and powerful bridge towards a fully electrified automotive future. Their direct approach to power delivery is not merely a technical detail, but a fundamental advantage that continues to engineer the future of driving.