The automotive world is constantly evolving, and perhaps no area has seen more innovative engineering than the development of hybrid powertrains. As a mechanic, delving into the intricacies of these systems reveals a fascinating interplay of mechanical and electrical components, all orchestrated to deliver efficiency and performance. At the heart of many hybrid vehicles lies a crucial distinction in how power is managed: the choice between series and parallel transmission configurations.

This deep dive will take you behind the scenes, offering a mechanic’s perspective on the fundamental differences between series, parallel, and the increasingly common series-parallel (power-split) hybrid systems. We will explore their operational principles, the unique advantages and disadvantages of each, and how these design choices impact everything from driving feel to long-term maintenance. Whether you are an automotive enthusiast, a fellow technician, or simply curious about the technology beneath the hood of your hybrid vehicle, understanding these distinctions is key to appreciating the engineering marvel that is a modern hybrid transmission.

Understanding the Core Concept: Hybrid Drivetrains

Before we dissect the different architectures, it is vital to grasp the foundational principles of a hybrid drivetrain. A hybrid vehicle combines at least two distinct power sources, typically an Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and an electric motor (or motors), to propel the vehicle. The primary goals are usually to improve fuel efficiency, reduce emissions, and sometimes enhance performance compared to a traditional internal combustion engine vehicle.

The core components of a hybrid system generally include:

- Internal Combustion Engine (ICE): The conventional gasoline or diesel engine that generates power.

- Electric Motor(s): One or more motors that can propel the vehicle, assist the ICE, and act as generators during deceleration (regenerative braking).

- Battery Pack: Stores electrical energy for the motors. These are typically high-voltage batteries (e.g., Nickel-Metal Hydride or Lithium-ion).

- Power Control Unit (PCU) / Inverter: The “brain” of the hybrid system, managing the flow of power between the battery, motors, and engine. It converts DC power from the battery to AC for the motors and vice-versa.

- Generator: In some configurations, a dedicated generator converts mechanical energy from the ICE into electrical energy. Often, an electric motor can serve dual roles as a motor and a generator.

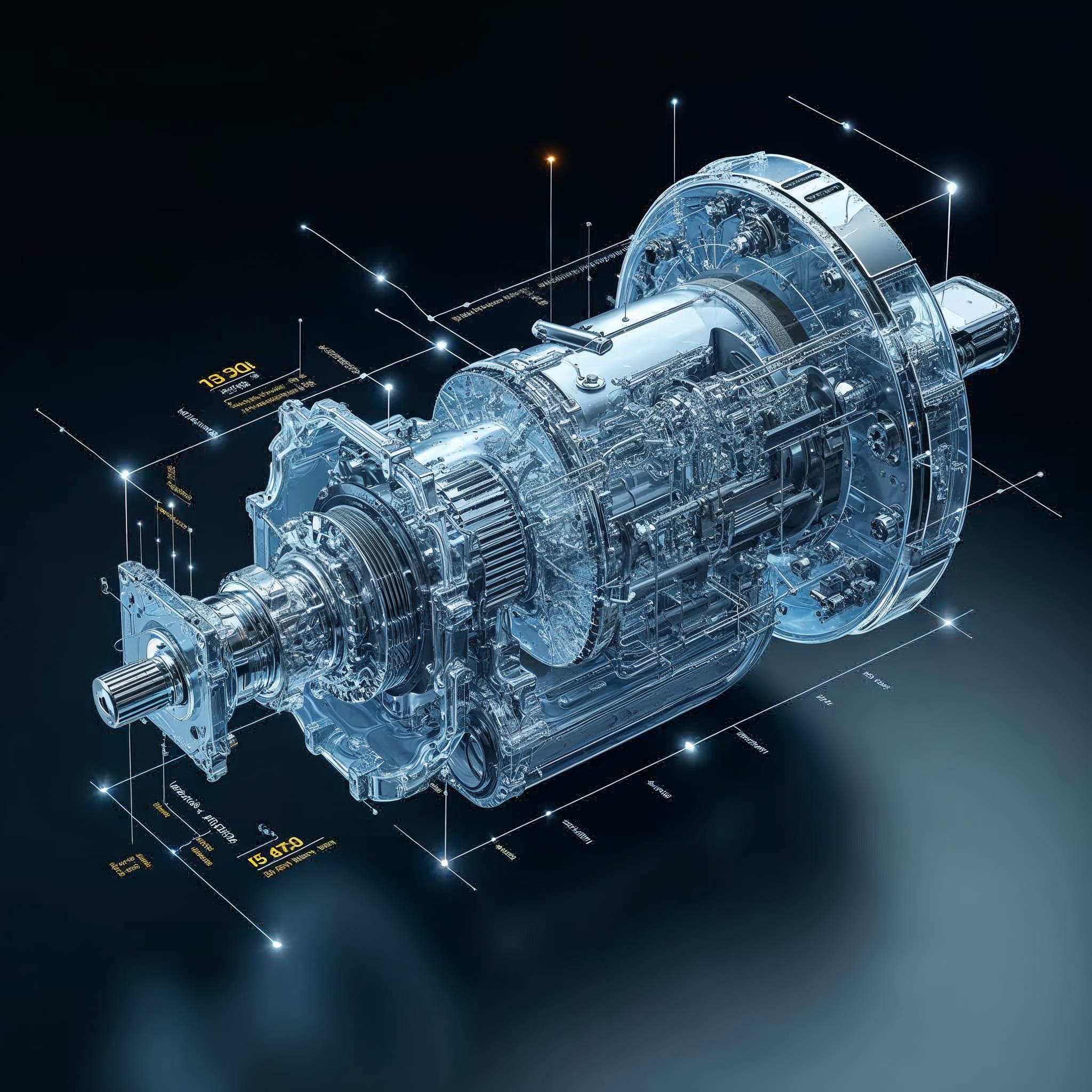

- Transmission/Transaxle: This component or system is what we are primarily focusing on. It manages the delivery of power from the ICE and/or electric motor(s) to the drive wheels. Unlike conventional transmissions, hybrid transmissions are often highly integrated and can be significantly more complex in their operation.

The magic of a hybrid lies in its ability to seamlessly switch between or combine these power sources, optimizing for the driving conditions. For instance, at low speeds or during acceleration, the electric motor can provide silent, emissions-free propulsion. During cruising, the ICE might take over, or both might work in tandem. During braking, kinetic energy is captured and converted back into electricity to recharge the battery – a process known as regenerative braking. The specific way these power sources are integrated and managed defines the hybrid transmission architecture, leading us to the series and parallel distinctions.

The Series Hybrid Configuration: Electric Drive First

Imagine an electric car with a built-in generator. That is essentially the simplest way to understand a series hybrid system. In this configuration, the Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) is never directly connected to the drive wheels. Instead, its sole purpose is to power a generator, which then produces electricity. This electricity can either be sent directly to the electric motor(s) that propel the vehicle or stored in the battery pack for later use.

How a Series Hybrid Works

- The ICE starts and drives a dedicated generator.

- The generator produces electricity.

- This electricity can:

- Charge the high-voltage battery.

- Directly power the electric drive motor(s).

- The electric drive motor(s) are the only components mechanically connected to the wheels, providing all propulsion.

From a driving perspective, a pure series hybrid feels very much like an electric vehicle (EV). Acceleration is smooth and linear, with no traditional gear shifts, as the electric motor provides continuous torque. The ICE comes on and off as needed to maintain battery charge or provide power for the electric motor, often at its most efficient RPM, decoupled from the vehicle’s speed.

Advantages of Series Hybrid Systems

- Smooth and Linear Power Delivery: Since only the electric motor drives the wheels, the driving experience is very smooth, similar to an EV, with instant torque and no gear changes.

- Optimal ICE Operation: The ICE can operate at its most efficient engine speed to generate electricity, irrespective of the vehicle’s speed. This means it can avoid inefficient low RPM or high RPM operations often experienced in urban stop-and-go traffic.

- Simplified Mechanical Drivetrain: No complex multi-speed transmission is needed to connect the ICE to the wheels, reducing mechanical complexity in that specific area.

- Excellent for Urban Driving: The system is highly effective in stop-and-go traffic where electric propulsion is frequently used, and the ICE can act purely as a range extender.

Disadvantages of Series Hybrid Systems

- Energy Conversion Losses: This is the primary drawback. Energy is converted multiple times: mechanical energy (ICE) to electrical energy (generator) to electrical energy storage (battery) to mechanical energy (electric motor). Each conversion incurs efficiency losses, which can make the system less efficient at higher speeds or constant power demands.

- Heavier Components: The electric motor(s) and generator need to be sized to handle the full power requirements of the vehicle, which often means larger and heavier components.

- Less Efficient at High Speeds: The double energy conversion becomes a significant efficiency penalty during sustained high-speed driving where the ICE would otherwise be very efficient if directly connected to the wheels.

Pure series hybrids are less common in mainstream passenger vehicles as the primary hybrid architecture due to these conversion losses. However, the concept is prevalent in range-extended electric vehicles (R-EVs) like the BMW i3 REx or some early versions of the Chevrolet Volt (though the Volt is actually a series-parallel hybrid with a strong series bias at times). They offer the benefits of electric driving with the assurance of a gasoline engine to recharge the battery when needed.

The Parallel Hybrid Configuration: Direct Power & Flexibility

In stark contrast to the series hybrid, a parallel hybrid system allows both the Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) and the electric motor to directly contribute power to the drive wheels, either individually or simultaneously. This configuration offers greater mechanical efficiency because power does not always have to undergo multiple energy conversions.

How a Parallel Hybrid Works

The key to a parallel hybrid is a mechanical coupling device, often a clutch, torque converter, or specialized gearbox, that allows the ICE and the electric motor to connect to the drivetrain. The electric motor is typically integrated between the engine and the conventional transmission (or transaxle).

Here’s how it operates:

- EV Mode: At low speeds or light loads, the electric motor can power the wheels independently, with the ICE shut off.

- ICE Mode: At higher speeds or when battery charge is low, the ICE can power the wheels directly, with the electric motor assisting or disengaged.

- Combined Mode (Parallel Assist): For maximum power (e.g., hard acceleration or hill climbing), both the ICE and the electric motor work together to drive the wheels.

- Regenerative Braking: During deceleration, the electric motor acts as a generator, recharging the battery.

The control system in a parallel hybrid is responsible for deciding which power source (or combination) is most appropriate for the current driving conditions, seamlessly engaging and disengaging the ICE as needed.

Advantages of Parallel Hybrid Systems

- Higher Mechanical Efficiency: Since both the ICE and electric motor can directly drive the wheels, there are fewer energy conversion losses, especially at higher speeds where the ICE can operate efficiently.

- Lighter and More Compact: The electric motor typically needs to be smaller than in a pure series hybrid because it does not have to provide all the propulsion alone; it primarily assists the ICE. This leads to a lighter overall system.

- More Traditional Driving Feel: Because the ICE is often directly coupled to the wheels and uses a conventional-style transmission, the driving experience can feel more familiar to drivers accustomed to gasoline cars, sometimes including gear shifts.

- Cost-Effective: Generally, parallel hybrid systems can be less expensive to manufacture than more complex series-parallel systems.

Disadvantages of Parallel Hybrid Systems

- More Complex Control System: Managing the seamless engagement and disengagement of the ICE and electric motor, along with potential gear shifts, requires sophisticated electronic control to avoid harsh transitions.

- ICE Not Always at Optimal Efficiency: Unlike series hybrids, the ICE in a parallel system is directly tied to vehicle speed, meaning it cannot always run at its most efficient RPM. This can lead to reduced efficiency in stop-and-go city driving.

- Packaging Challenges: Integrating the electric motor between the engine and transmission can sometimes pose packaging challenges, especially in existing vehicle platforms.

Examples of parallel hybrids include many mild hybrid systems (e.g., some Honda IMA systems, some Mercedes-Benz and Audi mild hybrids), where a small electric motor provides assist and regenerative braking. Full parallel hybrids, like some Hyundai and Kia models, feature larger motors capable of short-distance EV-only driving.

The Series-Parallel (or Power-Split) Hybrid: The Best of All Worlds?

Often considered the most sophisticated and widely adopted hybrid architecture, the series-parallel hybrid, also known as a power-split hybrid, cunningly combines elements of both series and parallel systems. Pioneered and popularized by Toyota with its Hybrid Synergy Drive (HSD), this design offers remarkable flexibility and efficiency across a broad range of driving conditions.

How a Series-Parallel Hybrid Works

The heart of a series-parallel system is typically a planetary gear set. This ingenious mechanical device has three inputs/outputs:

- Sun Gear: Connected to one of the electric motor/generators (MG1).

- Ring Gear: Connected to the drive wheels (and thus the output shaft).

- Planet Carrier: Connected to the Internal Combustion Engine (ICE).

A second electric motor/generator (MG2) is also connected to the drive wheels, usually coaxially with the ring gear or through a reduction gear. Through this planetary gear set, the system can dynamically blend power from the ICE and two motor-generators in various ways:

- Pure EV Mode: MG2 drives the wheels, MG1 and ICE are off or MG1 is spinning the ICE for battery charging.

- Series Mode: ICE drives MG1, which generates electricity to power MG2 (which drives the wheels) and/or charge the battery. The ICE is decoupled from the wheels.

- Parallel Mode: Both the ICE (via the planetary gear set) and MG2 (directly) drive the wheels for maximum power.

- ICE Charging Mode: The ICE drives MG1 to generate electricity, which charges the battery, while the vehicle is stationary or moving.

- Regenerative Braking: MG2 (and sometimes MG1) acts as a generator, converting braking energy back into electricity.

The beauty of this system lies in its ability to act as a continuously variable transmission (CVT) through electronic control of the motor-generators, providing seamless acceleration without traditional gear shifts. The power control unit constantly monitors driving conditions, driver input, and battery state of charge to determine the optimal power flow, adjusting the “virtual gear ratio” as needed.

Advantages of Series-Parallel Hybrid Systems

- Exceptional Flexibility: It can operate effectively as a series hybrid (for urban efficiency) or a parallel hybrid (for highway efficiency and combined power) depending on the situation.

- High Overall Efficiency: The system excels at optimizing ICE operation, allowing it to run at its most efficient points for power generation or propulsion, leading to impressive fuel economy across diverse driving cycles.

- Seamless and Smooth Operation: The electronically controlled CVT-like behavior provides incredibly smooth acceleration and deceleration, with imperceptible transitions between power sources.

- Strong Regenerative Braking: The dual motor-generator setup allows for very effective energy recovery during braking.

- Reliability: Despite the complexity, systems like Toyota’s HSD have proven to be remarkably reliable over decades.

Disadvantages of Series-Parallel Hybrid Systems

- Mechanical Complexity: The planetary gear set and the two motor-generators make the transaxle assembly quite intricate from an engineering and manufacturing standpoint.

- “Rubber Band” Effect: While smooth, some drivers perceive a disconnect between engine RPM and vehicle speed during hard acceleration, akin to a traditional CVT’s “rubber band” effect, where the engine might rev high but speed increases more gradually.

- Proprietary Technology: The core design is often heavily patented (e.g., Toyota’s HSD), requiring other manufacturers to develop their own variations or license the technology.

The vast majority of full hybrids and plug-in hybrids on the road today, including the Toyota Prius, Camry Hybrid, Ford Escape Hybrid, Lexus models, and many others, utilize some form of the series-parallel (power-split) architecture due to its superior efficiency and versatility.

Key Technical Differences and Mechanic’s Insights

From a mechanic’s perspective, understanding these distinctions goes beyond theoretical operation; it impacts diagnostics, repair strategies, and even what components are most likely to show wear or failure over time. Each architecture presents its own set of challenges and maintenance considerations.

Complexity and Componentry

- Series Hybrid: While the power path is simpler (ICE -> generator -> motor), the motors and generators need to be robust enough to handle full power. Less mechanical complexity in the *transmission* but potentially larger electrical components. A mechanic would focus on the integrity of the generator and drive motor, and the high-voltage cabling connecting them.

- Parallel Hybrid: Often uses a more conventional automatic transmission or manual transmission, with an integrated electric motor. The mechanical coupling (clutches, torque converters) between the ICE and motor is crucial. Diagnosis might involve traditional transmission issues alongside hybrid system faults.

- Series-Parallel (Power-Split): This is arguably the most mechanically complex in terms of its integrated transaxle (often called an eCVT or hybrid transaxle). The planetary gear set itself is robust, but the two motor-generators (MG1 and MG2), their associated windings, bearings, and the power control unit (inverter) that manages them, are critical points. Diagnostic tools need to be sophisticated to interpret the complex interplay of power flows.

Efficiency Profiles and Driving Characteristics

- Series Hybrid: Excels in urban stop-and-go driving due to its primary electric propulsion and the ICE operating at optimal points. Less efficient on the highway due to double conversion losses. Drivers experience smooth, EV-like acceleration.

- Parallel Hybrid: More mechanically efficient at higher speeds where the ICE can directly drive the wheels. Can be less efficient in heavy city traffic if the ICE has to frequently start/stop or operate inefficiently. Driving feel can be more traditional, with potential for more noticeable transitions between power sources.

- Series-Parallel: Offers a balanced efficiency profile, adapting well to both urban and highway conditions. The seamless power blending results in a very smooth driving experience, although some drivers might find the engine’s RPM decoupled from road speed during hard acceleration to be unusual.

Maintenance and Diagnostics

Regardless of the architecture, all hybrid systems share common high-voltage components that require specialized training and safety precautions. Key areas of focus for mechanics include:

- High-Voltage Battery Health: Degradation over time, cooling system integrity.

- Inverter/Converter Modules: These critical components manage high-voltage power; cooling system failures or internal component degradation can lead to expensive repairs.

- Electric Motor/Generator Windings and Bearings: While often robust, these can fail, sometimes due to overheating or internal shorts.

- Hybrid Transaxle Fluid: Specific fluid types and change intervals are crucial for lubricating and cooling the electric motors and planetary gears. This is often overlooked in comparison to traditional transmission fluid.

- High-Voltage Wiring: Inspect for damage, corrosion, or insulation breakdown.

- Control Module Software: Updates and recalibrations are often necessary to maintain optimal system performance.

Modern diagnostic tools are indispensable for hybrids. They can read specific hybrid system fault codes, monitor live data streams for battery cell voltages, motor temperatures, inverter states, and power flow. Understanding the unique operational characteristics of series, parallel, and series-parallel systems helps in quickly pinpointing whether an issue is related to the ICE, the electric system, or the way they are integrated.

The Evolution of Hybrid Transmissions: Recent Developments

The field of hybrid transmission technology is far from stagnant. Engineers are constantly innovating to improve efficiency, performance, and packaging. Recent developments show a trend towards more sophisticated integration and optimized performance across a wider range of driving conditions.

Multi-Speed Hybrid Transmissions

Traditionally, many hybrid systems, especially series-parallel types, functioned like eCVTs with no discrete gears. However, some manufacturers are now integrating multi-speed automatic transmissions with electric motors. For example:

- Hyundai/Kia’s D-HEV (Dedicated Hybrid Electric Vehicle) transmission: This system uses a conventional-style automatic transmission (e.g., a 6-speed dual-clutch transmission) with an electric motor integrated between the engine and the transmission. This allows for direct ICE connection and multiple gear ratios for improved efficiency and performance, particularly at higher speeds and for a more conventional driving feel.

- Mercedes-Benz 9G-Tronic with Integrated Starter Generator (ISG): While primarily a mild hybrid system, the ISG is often integrated directly into the transmission housing, allowing for powerful regenerative braking and torque assist through the existing gear ratios. More advanced versions are moving towards full plug-in hybrid integration.

- BMW eDrive systems: Many of BMW’s plug-in hybrids integrate the electric motor within the transmission housing, allowing for electric-only driving, combined power, and regenerative braking through a conventional ZF automatic transmission, offering a blend of performance and efficiency.

These developments aim to overcome the “rubber band” effect sometimes associated with eCVTs, providing a more direct and engaging driving experience while retaining hybrid efficiency benefits.

Increased Power Density and Sophisticated Control

Modern electric motors are becoming smaller, lighter, and more powerful, allowing for greater electric-only range and more potent hybrid assistance without adding significant weight. Battery technology continues to advance, with higher energy density allowing for smaller packs with greater capacity, leading to longer EV ranges for plug-in hybrids.

The control algorithms that manage the power flow are also becoming incredibly sophisticated. These systems can now predict driving conditions using navigation data, learn driver habits, and communicate with other vehicle systems (e.g., adaptive cruise control) to proactively optimize power usage and regenerative braking, maximizing efficiency.

Modular Hybrid Platforms

Many manufacturers are developing modular platforms that can accommodate various powertrain options – internal combustion, mild hybrid, full hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and even pure electric. This allows for greater flexibility in manufacturing and product development, as different hybrid architectures can be adapted to the same basic vehicle chassis, streamlining production and reducing costs.

These recent advancements underscore the continued investment in hybrid technology, not just as a stepping stone to full electrification, but as a viable and efficient solution that continues to evolve rapidly, offering a diverse range of options for consumers and presenting new learning opportunities for automotive technicians.

Comparison Tables

To help solidify the differences and advantages of each hybrid configuration, here are two comparison tables summarizing their key characteristics and applications.

| Feature | Series Hybrid | Parallel Hybrid | Series-Parallel (Power-Split) Hybrid |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICE Connection to Wheels | No direct mechanical connection; ICE only powers a generator. | Direct mechanical connection; ICE can drive wheels independently or with motor. | Variable mechanical connection via planetary gear set; ICE can drive wheels directly, or power generator, or both. |

| Primary Drive Source | Always electric motor(s). | ICE or electric motor, or both. | Electric motor(s) primarily at low speeds; ICE and motors at higher speeds or for combined power. |

| Energy Conversion Path | Mechanical (ICE) → Electrical (Generator) → Electrical (Motor) → Mechanical (Wheels). | Mechanical (ICE) → Mechanical (Wheels) OR Electrical (Motor) → Mechanical (Wheels). | Dynamic blending; can be series-like, parallel-like, or a combination. |

| Efficiency Profile | Excellent in urban driving; less efficient at high speeds due to double conversion. | Good at high speeds; can be less optimal in stop-and-go if ICE engages frequently. | Highly efficient across a wide range of driving conditions (urban & highway). |

| Drivetrain Complexity | Simpler mechanical transmission (no gears for ICE), but large motor/generator needed. | Moderate mechanical complexity (integration of motor with conventional transmission). | High mechanical complexity (planetary gear set, two motor-generators). |

| Driving Feel | Smooth, EV-like, linear acceleration. | More traditional, can have noticeable gear shifts/transitions. | Very smooth, seamless transitions, CVT-like (some “rubber band” effect perceived). |

| Typical Vehicle Type | Range-extended EVs (e.g., BMW i3 REx as primary example of pure series operating principle). | Mild hybrids, some full hybrids (e.g., Honda IMA, some Hyundai/Kia models with D-HEV). | Most modern full hybrids and plug-in hybrids (e.g., Toyota Prius, Ford Escape Hybrid, Lexus RX 450h). |

| Operational Mode | Series Hybrid Behavior | Parallel Hybrid Behavior | Series-Parallel Hybrid Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| EV-Only Driving | Default mode; electric motor always drives wheels. | Possible at low speeds/loads; electric motor directly drives wheels, ICE off. | Possible at low speeds/loads; MG2 drives wheels, ICE and MG1 off/idle. |

| ICE-Only Driving | Not possible; ICE only generates electricity. | Possible at higher speeds; ICE directly drives wheels, motor off/assist. | Possible at higher speeds; ICE directly drives wheels (via planetary gear), motors off/assist. |

| Combined Power (Acceleration) | Electric motor provides all power; ICE may generate more electricity for motor. | ICE and electric motor simultaneously drive wheels for maximum power. | ICE and both motor-generators (MG1, MG2) work in tandem to maximize output. |

| Battery Charging while Driving | ICE powers generator to charge battery (range extension). | ICE can power wheels and also charge battery via motor/generator; regenerative braking. | ICE can power MG1 to charge battery; regenerative braking via MG2. |

| Regenerative Braking | Electric motor converts kinetic energy to electricity for battery. | Electric motor converts kinetic energy to electricity for battery. | MG2 (and sometimes MG1) converts kinetic energy to electricity for battery. |

| Primary Advantage | Smooth, EV-like drive; ICE operates at peak efficiency as generator. | High mechanical efficiency; familiar driving feel; lighter system. | Exceptional flexibility; high overall efficiency; seamless power delivery. |

Practical Examples and Case Studies

Understanding the theory is one thing, but seeing these systems in real-world applications truly brings them to life. Here are some notable examples that illustrate the design philosophy behind each hybrid type:

The Pure Series Principle: The BMW i3 REx

While the BMW i3 is primarily an all-electric vehicle, its optional Range Extender (REx) version offers a brilliant real-world example of a series hybrid’s core principle. The i3 REx features a small 0.65-liter two-cylinder gasoline engine. This engine is never connected to the wheels. Its sole purpose is to power a generator, which then produces electricity to charge the battery and/or power the electric drive motor. This extends the vehicle’s range once the primary battery charge is depleted, alleviating range anxiety without adding the complexity of direct engine drive. Drivers experience continuous electric propulsion, with the small gasoline engine quietly humming in the background when needed, running at its most efficient RPM to top up the battery.

The Parallel Pioneer: Honda IMA (Integrated Motor Assist)

Honda’s Integrated Motor Assist (IMA) system, found in earlier generations of the Honda Insight, Civic Hybrid, and CR-Z, is a classic example of a parallel hybrid. In these vehicles, a thin electric motor is sandwiched directly between the internal combustion engine and a conventional transmission (often a CVT). The motor provides an “assist” to the engine during acceleration, acts as a generator during deceleration for regenerative braking, and can briefly propel the vehicle in EV-only mode at very low speeds or light loads. The ICE is the primary motivator, with the electric motor acting as a booster and energy recovery unit. This system was known for its simplicity and lightweight design, making it an efficient choice for compact vehicles, though its EV-only capabilities were limited compared to full hybrids.

The Series-Parallel Dominator: Toyota’s Hybrid Synergy Drive (HSD)

No discussion of hybrid transmissions would be complete without highlighting Toyota’s Hybrid Synergy Drive (HSD) system, which has become the gold standard for full hybrids globally. Found in popular models like the Toyota Prius, Camry Hybrid, RAV4 Hybrid, and various Lexus vehicles (e.g., RX 450h, ES 300h), HSD is a sophisticated series-parallel system. At its core is a planetary gear set (often referred to as the “power-split device”) that mechanically links the ICE with two motor-generators (MG1 and MG2) and the drive wheels. This allows the system to operate in pure EV mode, act as a series hybrid (ICE generating power for motors), or combine ICE and electric motor power in parallel for acceleration. The brilliance of HSD lies in its seamless blending of power, its high overall efficiency, and its proven reliability, making it the most successful hybrid architecture to date.

Modern Multi-Mode Parallel: Hyundai/Kia’s Dedicated Hybrid Transmissions

More recently, manufacturers like Hyundai and Kia have introduced sophisticated parallel hybrid systems that aim to deliver both efficiency and a more engaging driving experience. Their dedicated hybrid electric vehicle (D-HEV) transmissions, often using a 6-speed or 8-speed automatic or dual-clutch transmission, integrate a powerful electric motor between the engine and the gearbox. This allows for genuine multi-speed operation in both electric and hybrid modes, providing a more conventional “geared” driving feel compared to eCVTs. These systems can provide substantial EV-only range and robust combined power, representing a strong contender in the parallel hybrid space, particularly for those who prefer the feel of traditional shifting.

These examples illustrate that while the underlying principles remain, manufacturers adapt and innovate within these categories to meet specific market demands, whether it is maximizing urban EV range, achieving balanced overall efficiency, or delivering a more performance-oriented hybrid driving experience. For a mechanic, encountering these diverse systems means a need for continuous learning and specialized diagnostic approaches tailored to each architecture.

Frequently Asked Questions

Hybrid transmissions can be complex, and many drivers and even some technicians have questions about their operation and maintenance. Here are some frequently asked questions with detailed answers.

Q: What is the primary difference between series and parallel hybrids?

A: The primary difference lies in how the Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) connects to the wheels. In a series hybrid, the ICE never directly drives the wheels; it only generates electricity. The electric motor always propels the vehicle. In contrast, a parallel hybrid allows both the ICE and the electric motor to directly drive the wheels, either independently or together. This allows for greater mechanical efficiency in parallel systems but can result in more energy conversion losses in series systems at higher speeds.

Q: Which type of hybrid is more efficient in city driving?

A: Generally, a series hybrid tends to be more efficient in city driving. This is because the electric motor is the sole propulsion source, and the ICE can be optimized to run at its most efficient RPM to generate electricity when needed, rather than being tied to the varying speeds of stop-and-go traffic. Series-parallel systems also excel in city driving by effectively operating in a series-like mode, prioritizing electric propulsion.

Q: Which type is better for highway driving?

A: Parallel hybrids, and particularly series-parallel hybrids, are generally more efficient for highway driving. Parallel systems benefit from the ICE directly driving the wheels, minimizing energy conversion losses. Series-parallel systems can operate in a more parallel-like mode on the highway, ensuring the ICE provides direct power efficiently, avoiding the double conversion losses that can penalize pure series hybrids at sustained high speeds.

Q: What is a series-parallel hybrid, and how is it different from the other two?

A: A series-parallel hybrid, also known as a power-split hybrid (like Toyota’s HSD), combines elements of both series and parallel systems using a sophisticated planetary gear set. It can dynamically operate as a series hybrid (ICE generating electricity for motors) or a parallel hybrid (ICE and motor directly driving wheels), or a blend of both. This flexibility allows it to optimize efficiency across a very wide range of driving conditions, making it the most versatile and common type of full hybrid system today. It’s different because it’s not strictly one or the other, but an intelligent combination.

Q: Do hybrid transmissions require special maintenance?

A: Yes, hybrid transmissions often require specialized maintenance. While some fluid changes may be similar to conventional automatics, the hybrid transaxle fluid is often specific and crucial for cooling and lubricating integrated electric motors and complex gear sets. Additionally, maintenance requires technicians trained in high-voltage safety, as hybrids contain high-voltage components. Diagnostic tools also need to be specific to hybrid systems to accurately read and interpret unique fault codes and sensor data from the power control unit, battery, and motor-generators.

Q: Are hybrid batteries expensive to replace?

A: Hybrid battery replacement costs can vary significantly depending on the vehicle model, battery type (NiMH vs. Lithium-ion), and whether you opt for a new OEM battery, a reconditioned unit, or individual cell replacement. While new OEM batteries can be expensive (sometimes several thousands of dollars), the cost has decreased over time. Moreover, batteries are designed for the life of the vehicle and are typically warranted for 8-10 years or 100,000-150,000 miles, with some states offering longer warranties. Reconditioned options also provide a more affordable alternative.

Q: Can I drive a hybrid like a regular car?

A: Absolutely. Modern hybrids are designed to be driven just like any other automatic transmission vehicle. The sophisticated control unit seamlessly manages the interplay between the engine and electric motor, often making transitions imperceptible to the driver. While you can drive “normally,” adopting a smoother driving style with gentle acceleration and anticipating stops to maximize regenerative braking can significantly improve fuel economy.

Q: What are the common signs of a hybrid transmission problem?

A: Common signs of a hybrid transmission or hybrid system problem include a noticeable decrease in fuel economy, illuminated warning lights on the dashboard (such as the “Check Hybrid System” or “Malfunction Indicator Lamp”), unusual noises (whining, grinding, clunking) coming from the transaxle area, a loss of power or hesitation during acceleration, or inconsistent battery charging/discharging behavior. Any of these symptoms warrant immediate inspection by a qualified hybrid technician.

Q: How do PHEVs (Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles) fit into this?

A: Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs) typically use parallel or series-parallel hybrid architectures. The key difference is a larger battery pack that can be charged from an external power source (i.e., “plugged in”), allowing for a significantly extended all-electric driving range (typically 20-50+ miles) before the gasoline engine needs to engage. Once the battery is depleted, a PHEV operates like a conventional full hybrid, utilizing its series-parallel or parallel architecture for efficiency.

Q: Is one hybrid system inherently more reliable than another?

A: Reliability is more a function of specific engineering, manufacturing quality, and maintenance rather than the architecture itself. For example, Toyota’s Hybrid Synergy Drive (a series-parallel system) has an excellent reputation for long-term reliability. Similarly, well-engineered parallel systems can be very robust. Factors like proper cooling system design for high-voltage components, quality of battery management, and software calibration play a greater role in overall reliability than the architectural type alone.

Key Takeaways

Understanding the fundamental differences between hybrid transmission architectures is crucial for appreciating the innovation in modern vehicles. Here are the main points to remember:

- Series Hybrid: The Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) acts solely as a generator; an electric motor always drives the wheels. It offers a smooth, EV-like driving experience and excels in urban efficiency but suffers from energy conversion losses at higher speeds.

- Parallel Hybrid: Both the ICE and electric motor can directly drive the wheels. It provides greater mechanical efficiency, especially on highways, and often a more traditional driving feel. However, its control system can be complex, and ICE operation may not always be optimal in stop-and-go traffic.

- Series-Parallel (Power-Split) Hybrid: This architecture, epitomized by Toyota’s HSD, combines aspects of both series and parallel systems using a planetary gear set. It offers exceptional flexibility, high overall efficiency across all driving conditions, and very smooth power delivery. It is the most common full hybrid system today.

- Complexity and Maintenance: Each system has unique components and requires specialized diagnostic tools and technician training, particularly for high-voltage systems and specific fluid types.

- Recent Developments: The field is constantly evolving with multi-speed hybrid transmissions, increased power density in electric components, and sophisticated control algorithms enhancing performance and efficiency.

- Practical Application: Real-world examples like the BMW i3 REx (series principle), Honda IMA (parallel), and Toyota Prius (series-parallel) showcase these designs in action, each chosen for specific performance and efficiency goals.

Conclusion

The journey through the inner workings of hybrid transmissions reveals a world of intricate engineering, where the synergy between mechanical and electrical components dictates efficiency, performance, and the very nature of the driving experience. From the direct, often simpler approach of parallel systems to the generator-reliant elegance of series configurations, and finally to the masterful blending of series-parallel architectures, each design represents a thoughtful balance of trade-offs, aiming to solve the complex equation of sustainable mobility.

For us mechanics, this continuous evolution means a dynamic and challenging field, demanding a constant thirst for knowledge and adaptation. The days of simply looking at a transmission as a set of gears are long gone. Now, we must understand power electronics, battery management, sophisticated control algorithms, and the subtle dance between combustion and electric power.

As hybrid technology continues to advance, driven by the push for lower emissions and greater fuel economy, these diverse transmission strategies will remain at the forefront of automotive innovation. Whether you are a driver considering a hybrid, an enthusiast keen on understanding the latest tech, or a fellow mechanic preparing for the vehicles of tomorrow, a deep appreciation for ‘Inside Hybrid Transmissions’ is not just academic; it is essential for navigating the exciting, electrified future of automotive engineering.